"It is this similarity between the whole and its parts, even infinitesimal ones, that makes us consider this curve of von Koch as a line truly marvelous among all. If it were gifted with life, it would not be possible to destroy it without annihilating it whole, for it would be continually reborn from the depths of its triangles, just as life in the universe is."

E. Cesaro, Atti d. R. Accademia d. Scienze d. Napoli, 2, XII, number 15. [Excerpt from an article by Paul Lévy, reprinted in Edgar's text Classics on Fractals.]

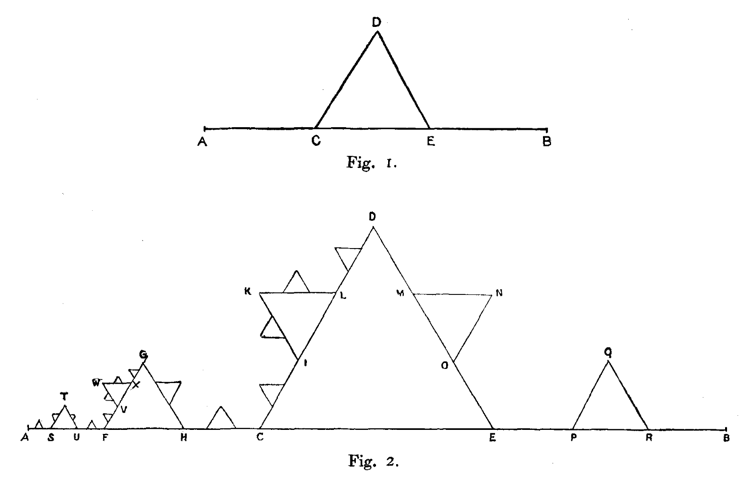

The Koch curve is the limiting curve obtained by applying this construction an infinite number of times. For a proof that this construction does produce a "limit" that is an actual curve, i.e. the continuous image of the unit interval, see the text [4] by Edgar.

|

\({f_1}({\bf{x}}) = \left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}}

1/3 & 0 \\

0 & 1/3 \\

\end{array}} \right]{\bf{x}}\) |

scale by r |

|

\({f_2}({\bf{x}}) = \left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}}

{1/6} & { - \sqrt 3 /6} \\

{\sqrt 3 /6} & {1/6} \\

\end{array}} \right]{\bf{x}} + \left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}}

{1/3} \\

0 \\

\end{array}} \right]\) |

scale by r, rotate by 60° |

|

\({f_3}({\bf{x}}) = \left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}}

{1/6} & { \sqrt 3 /6} \\

{- \sqrt 3 /6} & {1/6} \\

\end{array}} \right]{\bf{x}} + \left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}}

{1/2} \\

\sqrt 3 / 6 \\

\end{array}} \right]\) |

scale by r, rotate by −60° |

|

\({f_4}({\bf{x}}) = \left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}}

1/3 & 0 \\

0 & 1/3 \\

\end{array}} \right]{\bf{x}} + \left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}}

{2/3} \\

0 \\

\end{array}} \right]\) |

scale by r |

The fixed attractor of this IFS is the Koch curve.

\[\sum\limits_{k = 1}^4 {{r^d}} = 1 \quad \Rightarrow \quad d = \frac{{\log (1/4)}}{{\log (1/3 )}} = \frac{{\log (4)}}{{\log (3 )}} = 1.26186 \]

The length of the intermediate curve at the nth iteration of the construction is (4/3)n, where n = 0 denotes the original straight line segment. Therefore the length of the Koch curve is infinite. Moreover, as noted by Koch in his original article, the length of the arc between any two points on the curve is infinite since there is a copy of the Koch curve between any two points.

One of the other observations addressed in Koch's original paper was to evaluate the area contained between the curve and the initial horizontal chord of length 1, which Koch showed was \(\displaystyle \frac{1}{20}\sqrt{3}\) using the sum of a geometric series. This result can also be obtained by exploiting the self-similarity of the Koch curve [Details].

Three copies of the Koch curve placed outward around the three sides of an equilateral triangle form a simple closed curve that forms the boundary of the Koch snowflake. Three copes of the Koch curve placed so that they point inside the equilateral triangle create a simple closed curve that forms the boundary of the Koch anti-snowflake. Use the buttons below to toggle between the two options.

(4, 1/3)-Koch curve |

(5, 0.4)-Koch curve |

(6, 0.14)-Koch curve |

|

We can form a new IFS by applying each of the symmetries in G to each of the functions in K, i.e. form the set of affine transformations GK = { gf : g in G and f in K}. For example, if G = Z3, then the three elements of G are the identity (no rotation), r120, a counterclockwise rotation through 120°, and r240, a counterclockwise rotation through 240°. The new IFS would then consist of the 12 functions {fk, r120fk, r240fk for k = 1,2,3,4}. The first iteration would look like the following (using a horizontal line as the initial set as in the construction of the regular Koch curve).

This IFS again has a unique attractor, shown below, since each of the 12 affine transformations is contractive.

Notice that the self-similar parts of this fractal overlap, but that overall the fractal has three-fold rotational symmetry. If we rotate the fractal by 120°, then we are really just applying r120 to each of the 12 functions in the IFS. But this just permutes the elements of the IFS. For example, r120r120fk is just the same as r240fk since two rotations through 120° is the same as one rotation through 240°. So if A is the attractor for the IFS, then \[A = \bigcup\limits_{k = 1}^4 {\left( {{f_k}(A)\cup {{r_{120}}{f_k}(A)\cup {{r_{240}}{f_k}(A)} } } \right)} \] and rotating A by 120° yields \[\begin{align} {r_{120}}(A) &= {r_{120}}\left( {\bigcup\limits_{k = 1}^4 {\left( {{f_k}(A)\cup {{r_{120}}{f_k}(A)\cup {{r_{240}}{f_k}(A)} } } \right)} } \right) \\ &= \bigcup\limits_{k = 1}^4 {\left( {{r_{120}}{f_k}(A)\cup {{r_{240}}{f_k}(A)\cup {{f_k}(A)} } } \right)} = A \\ \end{align}\]

The four elements of the group Z4 produces rotational symmetry with angles of 0°, 90°, 180°, and 270°. Applying these to the Koch curve iterated system produces the following fractal with four-fold rotational symmetry. It is colored using pixel counting (the color depends on how many times a particular pixel is plotted during the drawing of the fractal using the random chaos game algorithm).

Here is the fractal obtained using the dihedral group D4. It is also colored using pixel counting. This fractal has both four-fold rotational symmetry (through rotations of 90°) as well as a reflective symmetry across horizontal, vertical, and diagonal lines. More details on symmetric fractals can be found here and in the book by Field and Golubitsky [15].